The mid-1970s were among the most challenging times the German Federal Republic ever faced. They were marred by terrorist attacks from the extreme leftist organization RAF. Their activities climaxed in September and October 1977, a period which has been dubbed “the German Autumn”. The president of the German Employers’ Confederation had been kidnapped in a violent attack in broad daylight, and Germany was on high alert. Police officers were in great danger, because the terrorists were armed and started shooting as soon as a police man looked at them with any kind of interest. Such an encounter had happened in Holland in mid September. Two police officer had walked into a restaurant and looked at three of the patrons for a few seconds too long, perhaps recognizing them as members of the RAF, when the young subjects drew machine guns and mowed down the officers before fleeing in a dark green VW bus with dutch plates. Days later, a young policeman at a road block accidentally fired a dozen rounds through the floor of a car because he had nervously clutched his unsecured automatic rifle while his colleagues were checking the passengers.

Into that atmosphere of fear and tension arrived two happy-go-lucky American friends of mine. They were blissfully unaware of any of this, and they decided to do what was a very common thing back then: Buy a VW van in Holland and drive through Europe in it.

The three of us had just driven across the US from California to New York, flown to Europe and after they bought the van, we met up in Heidelberg where I was studying at the time.

The morning after they arrived, the three of us hopped into the – dark green – van and drove to the post office. During the drive, I noticed a police car at a distance behind us. It followed us on every turn, and I mentioned it to my friend thinking that he might have committed an infraction. But since they oddly stayed at a distance and didn’t make a move, we decided to just continue on our drive.

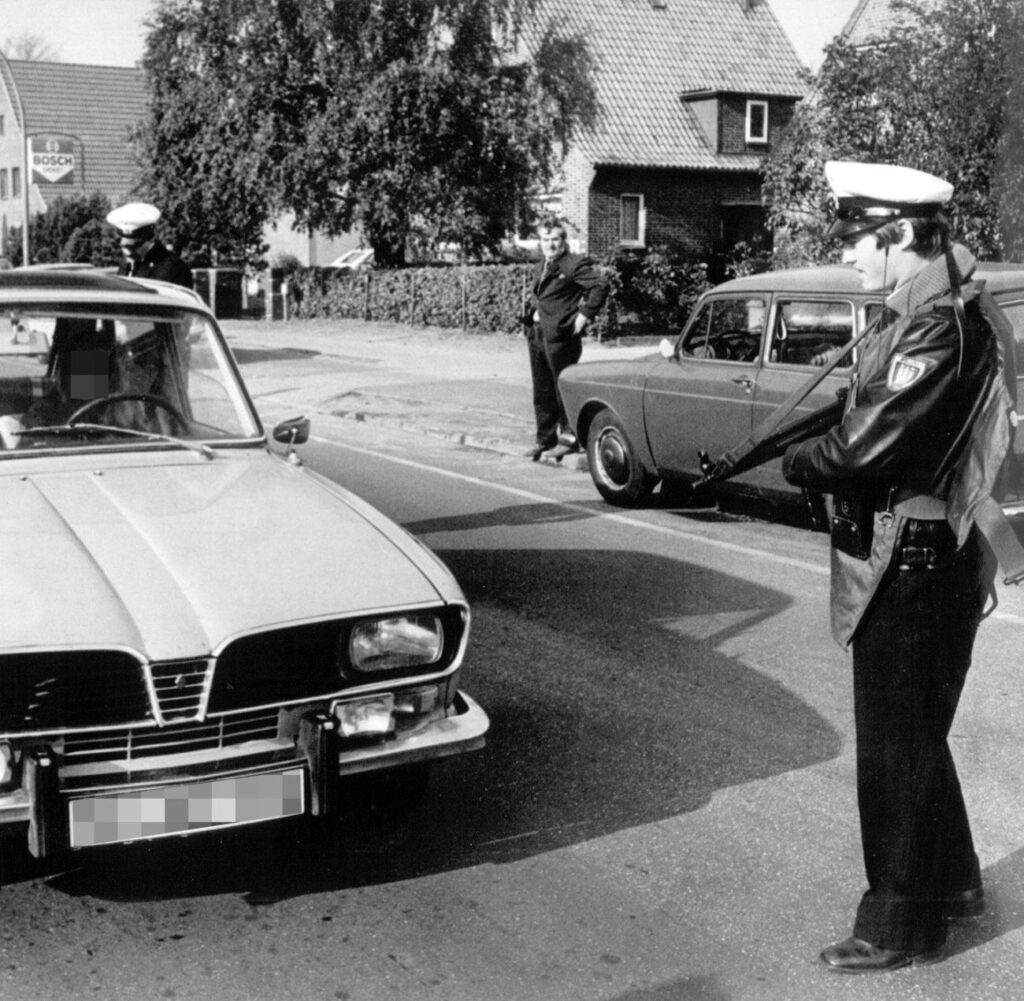

We parked in front of the post office and got out. At that moment half a dozen police cars came screeching around corners from all directions, and the officers swung the doors open, took cover behind them, pointed their machine guns at us and ordered us to stand with our hands against the wall.

I had heard of all the occurrences over the past days, and suddenly the danger of this situation became clear to me: Terrified cops with their finger on the trigger and the safety off on their guns, and the three of us shocked by the turn of events – it was a situation fraught with danger. One of my friends is a bit of a hot head, and I was afraid he might do something that could be misinterpreted, so I said to him in English, and in a loud voice so the cops would hear it: “Do exactly what they say! This is the most dangerous situation we’ve ever been in.” The other friend, who did not speak a word of German was simply terrified. I translated the command to her, and so the three of us stood facing the wall. After what seemed like an eternity, two heavily armed cops crept toward us and patted us down. In order to further diffuse the situation, I told them that we would be in full compliance, that my friends were tourists and that this obviously was a case of mistaken identity.

We were handcuffed and each of us put in the back of a separate police car. Next to me was an officer who couldn’t be more than 18 or 20 years old, whose face showed fear, and whose machine gun barrel was poking me in the ribs. It was my most uncomfortable ride ever, and probably my most dangerous one.

We were treated with the appropriate civility, and at the station we were locked into separate cells, waiting for the specialists from the BKA ( the German equivalent of the FBI) to fly in and identify us. I think by now the police officers suspected that it was a mistake, but they had to wait for confirmation by the federal specialists. By the time they arrived I had fallen asleep on the cot because of my jet-lag, and when they stepped into the cell one of them said: “Aw, look, he’s sleeping like a baby. No, that’s not him.”

We were released with apologies and were asked for understanding. They told us that a citizen had seen us driving in the van and called the police thinking that we were the terrorists involved in the shootout in Holland. I later saw their pictures and understood how that mistake was easy to make: Similar age, similar haircuts, same color VW van, dutch plates, and they were – as we – two men and a woman.

More shootouts happened that autumn, and every time I was reminded of how much could have gone wrong in those minutes. But luckily it didn’t.